Last evening, as left my friend’s neighborhood, a young man stopped me to ask if my car really gets 51 MPG. (Answer: yes, on the highway.) We had a long conversation through my passenger window about cars and engines, fuel types, automotive design. He indicated his 34-year-old Jeep Cherokee Chief, an orange behemoth that crouched behind him. He said, provocatively, My car is greener than yours; want to know why? With an impish gleam in his eye, standing there between our cars, he balanced one foot on his main mode of transport – his skateboard. He gave a brief dissertation on Lithium Ion, how environmentally damaging the mining is, how it can’t be recycled. (To be verified, I thought to myself. See below for more links.)

I said I wanted my next car to be no car and he said, yeah, get a bike. Smiling, he flipped the skateboard up and held it aloft. This is my other car.

Our conversation continued several minutes longer, touching on dual catalytic converters, combustion engines and fuel types. The exchange got me thinking again about the things our eco-guilt drives us to do or buy. Even though sometimes we unknowingly make choices that have an even worse impact, we go on thinking – at least in this one area – our hands are clean. I already have the fate / impact of my car’s original hybrid battery, replaced at 92,000 miles courtesy of Honda, on my scorecard. How do I know whether that offsets or even overshadows the gas efficiency and avoided emissions over the eight years I’ve driven it?

I wonder if this sort of dilemma (which we are usually unaware of) plays out with more frequency than we realize. We are so ensnared in modern industrial systems, it’s possible that purchasing a certain type of car hasn’t made much, or any, difference. It’s only by thinking up and up the stream, to get as close to the source as possible, we can start to unravel some of these entanglements.

For instance, wouldn’t it be better simply to walk my son to school, less than two miles away, rather than drive? I already work from home, so that’s done. We buy food locally as much as possible, especially in spring, summer and fall. We eat very little meat. As I understand it, these choices are meaningful.

Taking care when making substitutes can be a daunting responsibility. I recently ran across a discussion about the many forms of vinyl in building materials. The trick is, some alternatives may carry greater environmental penalties, if one factors in raw materials, manufacture, longevity, end-of-life recycling, and other life-cycle considerations. For example, PVC pipe for waste lines is far more long-lived than cast iron, which itself requires a coke furnace to forge (with attendant climate-changing emissions). The choices aren’t always as black and white as we might hope. In the case of pipe, there are fortunately other plastics that have a lighter environmental impact – ABS and HDPE, for example.

I’ve known for a while that our family’s next big hurdle is the energy use of our house, which was built in 1948 and is sorely in need of a good weatherizing. I’m more motivated by inspiring big-picture goals, such as weaning ourselves off fossil fuel altogether. Sure, we purchase 100% wind power through our electric utility, but what about the natural gas we use to heat our house and cook our food? For an anti-fracking girl, this is a rather sticky situation.

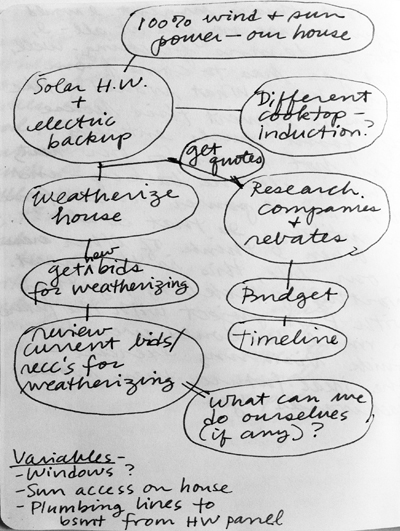

I felt a burst of excitement this morning when I used Hildy Gottlieb’s technique of a big vision plus reverse-engineering. From a no-fossil-fuel household, how do we get there, working backwards? The steps are clear: solar hot water panels, an electric induction cooktop, and – yes – weatherizing to minimize heat loss in winter. Now it’s time to roll up our sleeves and get started.

And those additional articles about lithium mining: “Cleaner than coal, but. . . .” and “Salt of the Earth,” about Bolivia’s lithium extraction industry.